Welch, K. (2012). Family Life Now (2nd Ed.). Boston. Allyn and Bacon Where Published

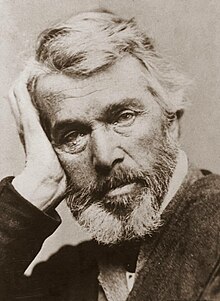

| Thomas Carlyle | |

|---|---|

Photo by Elliott & Fry, c.1860s | |

| Born | (1795-12-04)4 December 1795 Ecclefechan, Dumfriesshire, Scotland |

| Died | 5 Feb 1881(1881-02-05) (anile 85) London, England |

| Spouse(s) | Jane Welsh (thousand. 1826; died 1866) |

| Academic groundwork | |

| Education | Annan University |

| Alma mater | University of Edinburgh |

| Influences |

|

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | History, mathematics, philosophy |

| Notable works | Sartor Resartus (1836) The French Revolution (1837) On Heroes and Hero-Worship (1841) Occasional Soapbox (1849) History of Friedrich Two of Prussia (1858) |

| Notable ideas |

|

| Influenced |

|

| Signature | |

| |

Thomas Carlyle (four Dec 1795 – five Feb 1881) was a Scottish cultural critic, essayist, historian, lecturer, mathematician, novelist, philosopher and translator. Dubbed the "Sage of Chelsea," he exerted an enormous influence on the intellectual currents of the Victorian age; as George Eliot wrote in 1855, "there is hardly a superior or agile mind of this generation that has non been modified by Carlyle's writings."[1]

Carlyle's early study of High german enabled him to accept a conspicuous part in diffusing what was then a new intellectual light in the English-speaking world. Having lost organized religion in the Calvinism of his upbringing, he underwent what he called his spiritual new-nascency,[2] recounted in the "Wearing apparel Philosophy," Sartor Resartus, published 1833-1834. This was followed by The French Revolution: A History in 1837, the work that, with the Critical and Miscellaneous Essays, earned his fame, and established him as secular prophet.[3] In each of the years 1837 to 1840 he gave a grade of lectures, amid them On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and The Heroic in History, in which he asserted that "The History of the earth is but the Biography of groovy men." He would continue to cultivate his prophetic capacity in Past and Nowadays (1843), wherein he raised the "Status-of-England-Question," and further develop his doctrine of heroism with the issuance of Oliver Cromwell'southward Letters and Speeches, with Elucidations in 1845, which served to revise Cromwell's continuing. In response to the abolition movement, Carlyle published the "Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question" in 1849, followed by Latter-Day Pamphlets in 1850, in part an cess of the events of 1848. Both revealed Carlyle as radical reactionary; they sparked intense controversy. Afterward writing in 1851 a brief biography of his friend, The Life of John Sterling, he ended (1858-1865) his life'southward job with the History of Friedrich II of Prussia, Called Frederick the Great in six volumes; "the last and greatest of his works," in Froude's interpretation, and in Emerson's, "a Judgment 24-hour interval, for its moral verdict on men and nations, and the manners of modern times."[4]

Carlyle posthumously fell from grace upon publication of his Reminiscences as edited by James Anthony Froude, though enthusiasm persisted until the Edwardian era. Involvement revived in postwar years;[5] monuments were erected, and in 1936 his house on Cheyne Row was acquired by the National Trust, while his birthplace was acquired past the National Trust for Scotland. Later on the 2nd World War, Carlyle became associated[vi] with fascism due to his hierarchical views; his reputation subsequently declined. Since the 1970s, there has been something of a renaissance in Carlyle scholarship, with critical editions of his œuvre in steady product.[seven] [8] His writing has been described equally proto-postmodern.[9]

Early life and influences [edit]

Birthplace of Thomas Carlyle, Ecclefechan

Carlyle was built-in in 1795 in Ecclefechan in Dumfriesshire.[ten] His parents determinedly afforded him an education at Annan University, Annan, where he was bullied and tormented so much that he left after three years.[11] His father was a member of the Burgher secession Presbyterian church.[12] In early life, he was powerfully influenced past the strong Calvinist beliefs prevalent in his family and his nation.

After attending the University of Edinburgh, Carlyle became a mathematics teacher,[x] first in Annan and then in Kirkcaldy, where he became shut friends with the mystic Edward Irving. (Carlisle the historian and author is not to be confused with the lawyer Thomas Carlyle, built-in in 1803, who is besides connected to Irving via his work with the Catholic Apostolic Church.[13])

In 1819–21, Carlyle returned to the University of Edinburgh, where he suffered an intense crisis of faith and conversion, which provided the material for Sartor Resartus ("The Tailor Re-tailored"), which first brought him to the public'southward notice.

Carlyle developed a painful stomach ailment, perhaps gastric ulcers,[14] that remained throughout his life and likely contributed to his reputation as a crotchety, argumentative, somewhat bellicose personality. His prose style, famously cranky and occasionally savage, helped cement an air of irascibility.[xv]

Carlyle'south thinking became heavily influenced by German idealism, in particular, the work of Johann Gottlieb Fichte. He established himself as an skillful on German language literature in a serial of essays for Fraser's Magazine, and by translating German works, notably Goethe'due south novel Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre.[10] He also wrote a Life of Schiller (1825).[10]

In 1826, Thomas Carlyle married boyfriend intellectual Jane Baillie Welsh, whom he had met through Edward Irving during his menstruum of High german studies.[ten] In 1827, he applied for the Chair of Moral Philosophy at St Andrews Academy only was non appointed.[xvi] They moved to the chief house of Jane's small-scale agricultural estate at Craigenputtock, Dumfriesshire, Scotland.[10] He often wrote about his life at Craigenputtock – in particular: "It is certain that for living and thinking in I take never since found in the world a place so favourable." Here Carlyle wrote some of his most distinguished essays and began a lifelong friendship with the American essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson.[10]

In 1831, the Carlyles moved to London, settling initially in lodgings at 4 (now 33) Ampton Street, Kings Cross. In 1834, they moved to 5 (at present 24) Cheyne Row, Chelsea, which has since been preserved as a museum to Carlyle'due south memory. He became known as the "Sage of Chelsea", and a member of a literary circle which included the essayists Leigh Hunt and John Stuart Mill.[x]

Here Carlyle wrote The French Revolution: A History (three volumes, 1837), a historical study concentrating both on the oppression of the poor of French republic and on the horrors of the mob unleashed. The book was immediately successful.[ citation needed ]

Writing career [edit]

Early writings [edit]

By 1821, Carlyle abased the clergy as a career and focused on making a living as a writer. His first fiction, Cruthers and Jonson, was one of several bootless attempts at writing a novel.[ verification needed ] Following his work on a translation of Goethe's Wilhelm Meister'due south Apprenticeship,[10] he came to distrust the form of the realistic novel and so worked on developing a new form of fiction. In add-on to his essays on German literature, he branched out into wider-ranging commentary on modern culture in his influential essays Signs of the Times and Characteristics.[17] In the latter, he laid downwards his abiding preference for the natural over the artificial: "Thus, as we have an bogus Poetry, and prize but the natural; and so likewise we have an artificial Morality, an bogus Wisdom, an bogus Guild".[18] At this time he also penned articles appraising the life and works of various poets and men of messages, including Goethe, Voltaire and Diderot.

Sartor Resartus [edit]

His showtime major work, Sartor Resartus (lit. 'The Tailor Re-tailored'), was begun as a satirical article on "the philosophy of wearing apparel" and surprised him by growing into a total-length book. He wrote information technology in 1831 at the business firm on his married woman Jane's estate, Craigenputtock,[10] and it was intended to be a new kind of book: simultaneously factual and fictional, serious and satirical, speculative and historical. Ironically, information technology commented on its own formal structure while forcing the reader to confront the problem of where "truth" is to be found. Sartor Resartus was first published in instalments in Fraser's Magazine from 1833 to 1834.[10] The text presents itself as an unnamed editor'southward try to introduce the British public to Diogenes Teufelsdröckh, a German philosopher of clothes, who is, in fact, a fictional creation of Carlyle's. The Editor is struck with adoration, but for the most part is confounded by Teufelsdröckh's outlandish philosophy, of which the Editor translates choice selections.[19] To endeavour to make sense of Teufelsdröckh's philosophy, the Editor tries to slice together a biography, but with express success. Underneath the German philosopher'due south seemingly ridiculous statements, there are mordant attacks on Utilitarianism and the commercialisation of British lodge. The fragmentary biography of Teufelsdröckh that the Editor recovers from a chaotic mass of documents reveals the philosopher's spiritual journey.[20] He develops a contempt for the decadent condition of modern life. He contemplates the "Everlasting No" of refusal, comes to the "Centre of Indifference", and eventually embraces the "Everlasting Yea".[twenty] This voyage from denial to disengagement to volition would later on be described equally part of the existentialist awakening.

Given the genre-breaking nature of Sartor Resartus, it is not surprising that it at showtime achieved little attention. Its popularity developed over the side by side few years, and information technology was published as a single book in Boston 1836, with a preface by Ralph Waldo Emerson, influencing the development of New England Transcendentalism. The first British volume edition followed in 1838.

The Everlasting No and Yea [edit]

Watercolour sketch of Thomas Carlyle, historic period 46, by Samuel Laurence

"The Everlasting No" is Carlyle'due south proper noun for the spirit of unbelief in God, equally embodied in the Mephistopheles of Goethe, which is forever denying the reality of the divine in the thoughts, the character, and the life of humanity, and has a malicious pleasure in scoffing at everything high and noble as hollow and void.[21]

"The Everlasting Yea" is Carlyle'southward name in the book for the spirit of faith in God in an attitude of clear, resolute, steady, and uncompromising animosity to the "Everlasting No", and the principle that there is no such thing as faith in God except in such antagonism to the spirit opposed to God.[22]

In Sartor Resartus, the narrator[ specify ] moves from the "Everlasting No" to the "Everlasting Yea", but only through "The Centre of Indifference", a position of agnosticism and detachment. Merely after reducing desires and certainty, aiming at a Buddha-like "indifference", can the narrator realise affirmation. In some means, this is similar to the contemporary philosopher Søren Kierkegaard'due south "leap of faith" in Concluding Unscientific Postscript.

Worship of Silence and Sorrow [edit]

Following Goethe'southward description of Christianity as the "Worship of Sorrow", and "our highest faith, for the Son of Man", Carlyle interprets this equally "at that place is no noble crown, well worn or even ill worn, but is a crown of thorns".[23]

"The "Worship of Silence" is Carlyle's name for the sacred respect for restraint in speech till "idea has silently matured itself, ... to hold one's tongue till some meaning prevarication backside to set it wagging", a doctrine which many misunderstand, almost wilfully, information technology would seem; silence being to him the very womb out of which all dandy things are born."[24]

The French Revolution [edit]

In 1834, Carlyle and his wife left Craigenputtock for London and began to network in intellectual circles within the Great britain, establishing his ain reputation with the publication of his three-volume work The French Revolution: A History in 1837.[x] Subsequently the completed manuscript of the starting time volume was accidentally burned by a maid of the philosopher John Stuart Mill, Carlyle wrote the second and third volumes before rewriting the first from scratch.[eleven] [14]

The piece of work had a passion surprising in historical writing of that menstruation. In a politically charged Europe, filled with fears and hopes of revolution, Carlyle's account of the motivations and urges that inspired the events in France seemed powerfully relevant. Carlyle stressed the immediacy of action – often using the present tense – and incorporated dissimilar perspectives on the events he described.[25]

For Carlyle, chaotic events demanded what he called "heroes" to take control over the competing forces erupting within guild. While not denying the importance of economic and practical explanations for events, he saw these forces as "spiritual" – the hopes and aspirations of people that took the form of ideas, and were often ossified into ideologies ("formulas" or "isms", as he called them). In Carlyle's view, only dynamic individuals could principal events and straight these spiritual energies effectively: as presently equally ideological "formulas" replaced heroic human action, society became dehumanised.[ non-main source needed ] Like the opinions of many thinkers of the time, these ideas were influential on the development and rise of both socialism and fascism.[26]

Charles Dickens used Carlyle's work as a secondary source for the events of the French Revolution in his novel A Tale of Two Cities.[27] The book was also closely studied by Marking Twain during the terminal year of his life, and it was reported to be the concluding volume he read earlier his decease.

Heroes and Hero Worship [edit]

Carlyle moved towards his later on thinking during the 1840s, leading to a intermission with many old friends and allies, such equally Manufactory and, to a lesser extent, Emerson. His conventionalities in the importance of heroic leadership constitute class in the book On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and The Heroic in History, in which he was seen to compare a broad range of different types of heroes, including Odin, Muhammad, Oliver Cromwell, Napoleon, William Shakespeare, Dante, Samuel Johnson, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Robert Burns, John Knox, and Martin Luther.[28] These lectures of Carlyle'due south are regarded as an early and powerful formulation of the Great Human being theory of historical development.

For Carlyle, the hero was somewhat similar to Aristotle's "magnanimous" man – a person who flourished in the fullest sense. However, for Carlyle, unlike Aristotle, the world was filled with contradictions with which the hero had to deal. All heroes will be flawed. Their heroism lay in their artistic energy in the face of these difficulties, not in their moral perfection. To sneer at such a person for their failings is the philosophy of those who seek comfort in the conventional.[ non-primary source needed ] Carlyle chosen this "valetism", from the expression "no human is a hero to his valet."[29]

Past and Present [edit]

In 1843, he published his anti-democratic Past and Present, with its doctrine of ordered work.[30] In it, he influentially called attending to what he termed the "Condition of England" saying "England is full of wealth...supply for homo want in every kind; yet England is dying of inanition".[31] Past and Present combines medieval history with criticism of 19th-century British club. Carlyle wrote information technology in seven weeks as a respite from the harassing labour of writing Cromwell. He was inspired by the recently published Chronicles of the Abbey of Saint Edmund's Coffin, which had been written by Jocelin of Brakelond at the close of the 12th century. This account of a medieval monastery had taken Carlyle's fancy, and he drew upon it in guild to contrast the monks' reverence for work and heroism with the sham leadership of his own 24-hour interval.

After work [edit]

All these books were influential in their twenty-four hours, especially on writers such every bit Charles Dickens and John Ruskin. However, after the Revolutions of 1848 and political agitations in the United Kingdom, Carlyle published a drove of essays entitled Latter-Day Pamphlets, in 1850, in which he attacked democracy as an absurd social ideal, mocking the thought that objective truth could exist discovered past weighing up the votes for it, while as condemning hereditary aristocratic leadership as a "slow." The government should come up from those ablest to pb, Carlyle asserted. Two of these essays, No. I: "The Present Times" and No. II: "Model Prisons" was reviewed past Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in April 1850.[32] Marx and Engels state their approval of Carlyle's criticisms against hereditary elite; however, they harshly criticise Carlyle's views as "a thinly disguised acceptance of existing class dominion" and an unjust exoneration of statism.[33] Anthony Trollope for his part considered that in the Pamphlets "the grain of sense is then smothered in a sack of the sheerest trash.... He has one idea – a hatred of spoken and acted falsehood; and on this, he harps through the whole eight pamphlets".[34] A century later, Northrop Frye would similarly speak of the work as "tantrum prose" and "rhetorical ectoplasm."[35] [ unbalanced opinion? ]

In later writings, Carlyle sought to examine instances of heroic leadership in history. The Letters and Speeches of Oliver Cromwell (1845) presented a positive epitome of Cromwell: someone who attempted to weld gild from the conflicting forces of reform in his own twenty-four hours. Carlyle sought to make Cromwell's words live in their own terms by quoting him directly and then commenting on the significance of these words in the troubled context of the time. Again this was intended to make the past "present" to his readers: "he is epic, still living".[36]

His essay "Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question" (1849) suggested that slavery should never have been abolished, or else replaced with serfdom,[37] a view he shared with the Irish nationalist and later southern Confederate John Mitchel who, in 1846, had hosted Carlyle in Dublin.[38] Slavery had kept order, he argued, and forced work from people who would otherwise have been lazy and feckless: "West Indian blacks are emancipated and, it appears, refuse to work".[39] John Carey in "The truculent genius of Thomas Carlyle", a review in Books and Bookmen in 1983, says: "The standard view, which is that Carlyle was and so poisonous it's a wonder his mind didn't infect his bloodstream." On Carlyle'south attitude to slavery he adds: "Carlyle was a racist, with a rare talent for misreading historical trends."[ citation needed ] Likewise, Charles Darwin, in his autobiography, called his views of slavery "Revolting. In his eyes might was right."[40] This view, and Carlyle's support for the repressive measures of Governor Edward Eyre in Jamaica during the Morant Bay rebellion,[thirty] further alienated him from his one-time liberal allies. As Governor of the Colony, Eyre, fearful of an isle-wide uprising, forcibly suppressed the rebellion and had many black peasants killed. Hundreds were flogged. He likewise authorised the execution of George William Gordon, a mixed-race colonial assemblyman who was suspected of involvement in the rebellion. These events created great controversy in Great britain, resulting in demands for Eyre to be arrested and tried for murdering Gordon. John Stuart Mill organised the Jamaica Committee, which demanded his prosecution and included some well-known British liberal intellectuals (such as John Bright, Charles Darwin, Frederic Harrison, Thomas Hughes, Thomas Henry Huxley, and Herbert Spencer).

Carlyle fix rival Governor Eyre Defence and Aid Committee for the defense, arguing that Eyre had acted decisively to restore gild.[41] His supporters included John Ruskin, Charles Kingsley, Charles Dickens, Alfred Tennyson and John Tyndall. Eyre was twice charged with murder, just the cases never proceeded.

Like difficult-line views were expressed in Shooting Niagara, and After?, written later on the passing of the Electoral Reform Act of 1867 in which he "reaffirmed his conventionalities in wise leadership (and wise followership), his atheism in democracy and his hatred of all workmanship – from brickmaking to diplomacy – that was non genuine."[42]

Frederick the Not bad [edit]

His last major work was History of Friedrich 2 of Prussia, an epic life of Frederick the Slap-up (1858–1865). In this Carlyle tried to prove how a heroic leader can forge a state, and help create a new moral culture for a nation. For Carlyle, Frederick epitomised the transition from the liberal Enlightenment ideals of the eighteenth century to a new modern civilization of spiritual dynamism embodied by Frg, its thought and its polity. The book is almost famous for its vivid, arguably very biased,[ verification needed ] portrayal of Frederick's battles, in which Carlyle communicated his vision of nearly overwhelming chaos mastered by the leadership of genius.[ non-primary source needed ]

Carlyle struggled to write the book, calling it his "Thirteen Years War" with Frederick. Some of the nicknames he came upward with for the work included "the Nightmare", "the Minotaur", and "the Unutterable book".[43] In 1852, he made his get-go trip to Germany to gather fabric, visiting the scenes of Frederick's battles and noting their topography. He made another trip to Germany to study battlefields in 1858. The piece of work comprised six volumes; the first two volumes appeared in 1858, the third in 1862, the quaternary in 1864 and the last ii in 1865. Emerson considered information technology "Infinitely the wittiest book that was always written." James Russell Lowell pointed out some faults, but wrote: "The figures of most historians seem like dolls stuffed with bran, whose whole substance runs out through any hole that criticism may tear in them; but Carlyle'due south are so real in comparison, that, if you prick them, they drain." The piece of work was studied as a textbook in the military academies of Germany.[44] [45] David Daiches, even so, later concluded that "since his 'thought' of Frederick is non actually borne out by the prove, his mythopoeic effort partially fails".[thirty]

The effort involved in the writing of the volume took its cost on Carlyle, who became increasingly depressed, and subject field to diverse probably psychosomatic ailments. In 1853 he wrote a letter to his sis describing the construction of a small penthouse room over his home in Chelsea, intended as a soundproof writer's room. Unfortunately, the skylight fabricated information technology "the noisiest room in the firm".[43] The mixed reception to the book likewise contributed to Carlyle'due south decreased literary output.

Last works [edit]

Later on writings were mostly short essays, notably the unsuccessful The Early Kings of Norway,[46] a serial on early on-medieval Norwegian warlords. Also An Essay on the Portraits of John Knox appeared in 1875, attempting to bear witness that the best-known portrait of John Knox did not describe the Scottish prelate. This was linked to Carlyle'southward long involvement in historical portraiture, which had before fuelled his project to found a gallery of national portraits, fulfilled past the creation of the National Portrait Gallery, London and the Scottish National Portrait Gallery. He was elected a Strange Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1878.[47]

London Library [edit]

Carlyle was the chief instigator in the foundation of the London Library in 1841.[48] [49] He had go frustrated by the facilities bachelor at the British Museum Library, where he was often unable to observe a seat (obliging him to perch on ladders), where he complained that the enforced close confinement with his young man readers gave him a "museum headache", where the books were unavailable for loan, and where he found the library's collections of pamphlets and other material relating to the French Revolution and English language Civil Wars inadequately catalogued. In particular, he developed an antipathy to the Keeper of Printed Books, Anthony Panizzi (despite the fact that Panizzi had immune him many privileges not granted to other readers), and criticised him, as the "respectable Sub-Librarian", in a footnote to an article published in the Westminster Review.[50] Carlyle's eventual solution, with the back up of a number of influential friends, was to phone call for the establishment of a individual subscription library from which books could be borrowed.

Personal life [edit]

Portrait of Carlyle in his garden at Chelsea

Carlyle had a number of would-be romances before he married Jane Welsh, an important literary figure in her own right. The virtually notable were with Margaret Gordon, a pupil of his friend Edward Irving. Even after he met Jane, he became enamoured of Kitty Kirkpatrick, the daughter of a British officer and a Mughal princess. William Dalrymple, writer of White Mughals, suggests that feelings were mutual, simply social circumstances made the union impossible, equally Carlyle was so poor. Both Margaret and Kitty accept been suggested every bit the original of "Blumine", Teufelsdröckh'due south love, in Sartor Resartus.[51]

Thomas besides had a friendship with the author Geraldine Jewsbury starting in 1840. During that twelvemonth Jewsbury was going through a depressive state and too experiencing religious doubt. She wrote to Carlyle for guidance and also thanked him for his well-written essays. Somewhen, Carlyle invited Jewsbury out to Cheyne Row, where Carlyle and Jane resided. Jewsbury and Jane from and so on had a close friendship and Carlyle likewise helped Jewsbury get on to the English literary scene.[52]

Marriage [edit]

Carlyle married Jane Welsh in 1826.[53] He met Welsh through his friend and her tutor Edward Irving, with whom she came to have a mutual romantic (although not intimate) attraction. Welsh was the subject of Leigh Hunt's poem, "Jenny buss'd Me".[54]

Their marriage proved to be one of the most famous, well documented, and unhappy of literary unions.[55]

It was very good of God to allow Carlyle and Mrs Carlyle marry one another, and so brand only two people miserable and not four.

Carlyle became increasingly alienated from his wife. Carlyle's biographer James Anthony Froude published (posthumously) his opinion that the wedlock remained unconsummated due to impotence.[57] Frank Harris also suspected Carlyle of impotence.[58]

Although she had been an invalid for some time, his wife's sudden death in 1866 was unexpected and it greatly distressed Carlyle who was moved to write his highly self-critical "Reminiscences of Jane Welsh Carlyle", published posthumously.[59]

Afterwards life [edit]

Carlyle was named Lord Rector of Edinburgh Academy. Iii weeks afterwards his inaugural accost there, Jane died, and he partly retired from agile order. His terminal years were spent at 24 Cheyne Row (and so numbered five), Chelsea, London SW3 (which is at present a National Trust property[60] commemorating his life and works) but he hankered after a render to Craigenputtock.

Death [edit]

Upon Carlyle'south decease on 5 February 1881, it is a measure of his standing that interment in Westminster Abbey was offered; this was rejected by his executors due to Carlyle's expressed wish to exist cached abreast his parents in Ecclefechan.[59] His final words were, "Then, this is expiry. Well!"[61]

Biography [edit]

Carlyle would have preferred that no biography of him was written, just when he heard that his wishes would not be respected and several people were waiting for him to die before they published, he relented and supplied his friend James Anthony Froude with many of his and his married woman'southward papers. Carlyle'due south essay about his married woman was included in Reminiscences, published shortly after his expiry by Froude, who also published the Messages and Memorials of Jane Welsh Carlyle annotated past Carlyle himself. Froude'southward Life of Carlyle was published over 1882–84. The frankness of this book was unheard of past the normally respectful standards of 19th-century biographies of the period.[62] Froude'due south piece of work was attacked by Carlyle's family, especially his nephew, Alexander Carlyle[63] and his niece, Margaret Aitken Carlyle. All the same, the biography in question was consistent with Carlyle's own conviction that the flaws of heroes should be openly discussed, without diminishing their achievements. Froude, who had been designated by Carlyle himself as his biographerhoped-for, was acutely aware of this belief. Froude's defense force of his decision, My Relations With Carlyle, was published posthumously in 1903, including a reprint of Carlyle's 1873 will, in which Carlyle equivocated: "Limited biography of me I had really rather that there should exist none." Nevertheless, Carlyle in the will simultaneously and completely deferred to Froude'south judgment on the matter, whose "conclusion is to exist taken equally mine."[64]

Views [edit]

Anglo-Saxonism [edit]

Described every bit ane of the "almost adamant protagonists" of Anglo-Saxonism,[65] Carlyle considered the Anglo-Saxon race as superior to all others.[66] In his lifetime, his shared Anglo-Saxonism with Ralph Waldo Emerson was described as a defining trait of their friendship.[67] Sometimes critical of the United States, describing information technology every bit a "formless" Saxon tribal club, he suggested that the Normans had provided Anglo-Saxons with a superior sense of club for national construction in England.[68]

Antisemitism [edit]

Carlyle held staunchly anti-Jewish views. Invited by Baron Rothschild in 1848 to support a Beak in Parliament to permit voting rights for Jews in the Uk, Carlyle declined to offer his support to what he named the "Jew Bill". In a correspondence with Richard Monckton Milnes he insisted that Jews were hypocritical to want access into the British Parliament, suggesting that a "existent Jew" could only exist a representative or denizen of "his ain wretched Palestine", and in this context, alleged that all Jews should be expelled to Palestine.[69] He was publicly criticised by Charles Dickens for his "well-known aversion to the Jews".[seventy] Playing into deeply anti-semitic stereotypes, Carlyle identified Jews with materialism and archaic forms of religion, attacking both the East London communities of Jewish orthodoxy and "West Stop" Jewish wealth, which he perceived equally cloth abuse.[71]

Christianity [edit]

Carlyle had once lost his religion in Christianity while attending the Academy of Edinburgh, later adopting a form of deism[72] or "restatement" of Christianity, according to Charles Frederick Harrald "a Calvinist without the theology".[73]

Legacy [edit]

Carlyle painted by John Everett Millais. Froude wrote of this painting:

under Millais's hands the one-time Carlyle stood again upon the canvas as I had not seen him for thirty years. The inner secret of the features had been plain caught. There was a likeness which no sculptor, no photographer, had nevertheless equaled or approached. Afterward, I knew not how information technology seemed to fade abroad.

Thomas Carlyle is notable both for his continuation of older traditions of the Tory satirists of the 18th century in England and for forging a new tradition of Victorian era criticism of progress known as sage writing.[74] Sartor Resartus can exist seen both equally an extension of the cluttered, sceptical satires of Jonathan Swift and Laurence Sterne and equally an enunciation of a new signal of view on values.

Carlyle is also important for helping to introduce German Romantic literature to Uk. Although Samuel Taylor Coleridge had too been a proponent of Schiller, Carlyle'southward efforts on behalf of Schiller and Goethe would carry fruit.[75]

The reputation of Carlyle's early work remained high during the 19th century but declined in the 20th century. George Orwell called him "a master of belittlement. Even at his emptiest sneer (as when he said that Whitman thought he was a big human being because he lived in a big country) the victim does seem to compress a little. That [...] is the power of the orator, the man of phrases and adjectives, turned to a base use."[76] However, Whitman himself described Carlyle as lighting "up our Nineteenth Century with the calorie-free of a powerful, penetrating and perfectly honest intellect of the kickoff-class" and "Never had political progressivism a foe it could more heartily respect".[77]

Thomas Carlyle had a popular reception in the United States.[78] [79] In the nineteenth century, many Antebellum Southerners considered Carlyle to exist a champion of slavery.[80] His influence was so pervasive that the journal The Southern Quarterly Review boasted that 'The spirit of Thomas Carlyle is away in the land.'[81] Withal, Carlyle likewise influenced extremist views in the Antebellum South. Carlyle had a profound impact on the Southern intellectual George Fitzhugh's notions of palingenesis, multi-racial slavery, and absolutism.[82] In the twentieth century, Carlyle'south attacks on the ills of industrialisation and on classical economics were an important inspiration for U.Southward. progressives.[83] In item, Carlyle criticised JS Mill's economic ideas for supporting Black Emancipation past arguing that Blacks' socio-economic status depended on economical opportunities rather than heredity.[84] Carlyle's racist justification for economic statism evolved into the elitist and eugenicist "intelligent social engineering" promoted early by the progressive American Economical Association.[85]

His reputation in Deutschland was always loftier, because of his promotion of German thought and his biography of Frederick the Great. Friedrich Nietzsche, whose ideas are comparable to Carlyle's in some respects,[86] [87] was dismissive of his moralism, calling him an "absurd muddlehead" in Across Good and Evil [88] and regarded him equally a thinker who failed to free himself from the very little-mindedness he professed to condemn.[89] Carlyle's distaste for democracy[90] and his belief in charismatic leadership was appealing to Joseph Goebbels, who frequently referenced Carlyle's piece of work in his periodical,[91] and read his biography of Frederick the Great to Hitler during his final days in 1945.[75] [92] Many critics in the 20th century identified Carlyle as an influence on fascism and Nazism.[75] Ernst Cassirer argued in The Myth of the State that Carlyle'southward hero-worship contributed to 20th-century ideas of political leadership that became part of fascist political ideology.[93] Farther evidence for this argument can be plant in letters sent by Carlyle to Paul de Lagarde, one of the early proponents of the Fuehrer principle.[91]

Sartor Resartus has recently been recognised over again equally a remarkable and significant work, arguably anticipating many major philosophical and cultural developments, from Existentialism to Postmodernism.[94] Information technology has been argued that his critique of ideological formulas in The French Revolution provides a practiced account of the ways in which revolutionary cultures turn into repressive dogmatism.

Essentially a Romantic, Carlyle attempted to reconcile Romantic affirmations of feeling and freedom with respect for historical and political fact. Many believe that he was always more than attracted to the idea of heroic struggle itself than to any specific goal for which the struggle was existence made. Withal, Carlyle'due south conventionalities in the connected use to humanity of the Hero, or Not bad Man, is stated succinctly at the end of his essay on Muhammad (in On Heroes, Hero-Worship & the Heroic in History), in which he concludes that: "the Slap-up Man was e'er as lightning out of Heaven; the residual of men waited for him similar fuel, and and then they too would flame."[95]

A bosom of Carlyle is in the Hall of Heroes of the National Wallace Monument in Stirling.

The Carlyle Hotel in New York is named subsequently him.

The name of One, Inc. was derived from an aphorism by Carlyle: "A mystic bond of brotherhood makes all men one".[96]

The American blogger and founder of the Neoreactionary motility Curtis Yarvin cites Carlyle as being his chief inspiration stating "I'one thousand a Carlylean more than or less the manner a Marxist is a Marxist."[97]

Works [edit]

- (1829) Signs of the Times. The Victorian Web

- (1833–34) Sartor Resartus. Project Gutenberg

- (1837) The French Revolution: A History. Project Gutenberg

- (1840) Chartism. Google Books

- (1841) On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and The Heroic in History. Projection Gutenberg

- (1843) Past and Present. Project Gutenberg

- (1845) Oliver Cromwell's Messages and Speeches, with Elucidations, ed. Thomas Carlyle, 3 vol. (often reprinted).[98] Online version. Some other online version.

- (1849) "Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question", Fraser's Magazine (anonymous), Online text

- (1850) Latter-Day Pamphlets. Project Gutenberg

- (1851) The Life of John Sterling. Project Gutenberg

- (1858) History of Friedrich 2 of Prussia. Index to Project Gutenberg texts

- (1867) Shooting Niagara: and Later. Online Text

- (1875) The Early Kings of Norway. Project Gutenberg

- (1882) Reminiscences of my Irish gaelic Journeying in 1849. Online text

- (1892) Lectures on the History of Literature

In that location are several published "Collected Works" of Carlyle:

Unauthorized lifetime editions:

- "Thomas' Carlyle'due south Ausgewählte Schriften", 1855–56, Leipzig. Translations by A. Kretzschmar. Abandoned afterwards half dozen vols.

Authorised lifetime editions:

- Compatible edition, Chapman and Hall, 16 vols, 1857–58.

- Library edition, Chapman and Hall, 34 vols (30 vols 1869–71, iii boosted vols added 1871 and ane more 1875). The most lavish lifetime edition, it sold for 6 to ix shillings per book (or £15 the set)

- People's edition, Chapman and Hall, 39 vols (37 vols 1871–74, with 2 extra volumes added in 1874 and 1878). Carlyle insisted the toll be kept to ii shillings per book.

- Chiffonier edition, Chapman and Hall, 37 vols in 18, 1874 (printed from the plates of the People's Edition)

Posthumous editions:

- Centennial edition, Chapman and Hall, thirty vol, 1896–99 (with reprints to at least 1907). Introductions by Henry Duff Traill. The text is based on the People's edition, and it is used past many scholars as the standard edition of Carlyle's works.

- Norman and Charlotte Strouse edition (originally the California Carlyle edition), University of California Press, 1993–2006. Only 4 volumes were issued: On Heroes (1993), Sartor Resartus (2000), Historical Essays (2003) and By and Nowadays (2006). Despite being incomplete, information technology is the simply critical edition of (some of) Carlyle's works.

Definitions [edit]

Carlyle coined a number of unusual terms, which were collected by the Nuttall Encyclopedia. Some include:

- Heart of Immensities

- An expression of Carlyle'due south to signify that wherever any one is, he is in touch with the whole universe of existence, and is, if he knew it, as near the heart of it there as anywhere else he can be.

- Eleutheromania

- A mania or frantic zeal for freedom.

- Gigman

- Carlyle's name for a man who prides himself on, and pays all respect to, respectability. It is derived from a definition once given in a courtroom of justice by a witness who, having described a person equally respectable, was asked by the judge in the case what he meant by the give-and-take; "1 that keeps a gig", was the reply. Carlyle also refers to "gigmanity" at large.

- Hallowed Fire

- An expression of Carlyle'due south in definition of Christianity "at its rise and spread" as sacred, and kindling what was sacred and divine in man's soul, and burning up all that was not.

- Logic Spectacles

- Eyes that tin can discern only the external relations of things, but not the inner nature of them.[99]

- Mights and Rights

- The Carlyle doctrine that Rights are nothing till they have realised and established themselves as Mights; they are rights first only so.

- Pig-Philosophy

- The name given by Carlyle in his word of Jesuitism in his Latter-Day Pamphlets to the widespread philosophy of the time, which regarded the human being every bit a mere creature of appetite instead of a brute of God endowed with a soul, with no nobler idea of well-being than the gratification of want – that his only Heaven, and the reverse of it his Hell.

- Plugston of Undershot

- Carlyle's proper noun for a "captain of industry" or fellow member of the manufacturing grade.

- Present Fourth dimension

- Defined by Carlyle as "the youngest born of Eternity, child and heir of all the past times, with their practiced and evil, and parent of all the future with new questions and significance", on the right or incorrect agreement of which depend the issues of life or death to usa all, the sphinx riddle given to all of the states to rede as we would live and non dice.

- Prinzenraub (the stealing of the princes)

- Name given to an attempt to satisfy a private grudge, referring to the attempted kidnapping by Kunz von Kaufungen in 1455 of two immature Saxon princes from the castle of Altenburg, in which he was apprehended past a collier named Schmidt, handed over to the authorities, and beheaded. (See Carlyle's business relationship of this in his Miscellanies.)

- Printed Paper

- Carlyle's satirical proper name for the literature of French republic prior to the Revolution.

- Progress of the Species Magazines

- Carlyle's name for the literature of the day which does nada to help the progress in question, only keeps idly boasting of the fact, taking all the credit to itself, like French poet Jean de La Fontaine'southward fly on the beam of the careening chariot soliloquising, "What a grit I heighten!"

- Sauerteig

- (i.due east. leaven), an imaginary authority alive to the "celestial infernal" fermentation that goes on in the world, who has an eye specially to the evil elements at work, and to whose stance Carlyle frequently appeals in his condemnatory verdict on sublunary things.

- The Conflux of Eternities

- Carlyle'due south phrase for time, as in every moment of it a centre in which all the forces to and from eternity see and unite, so that past no past and no future can nosotros exist brought nearer to Eternity than where we at whatsoever moment of Time are; the Nowadays Time, the youngest born of Eternity, being the child and heir of all the Past times with their skilful and evil, and the parent of all the Future. Past the import of which (see Matt. xvi. 27), information technology is accordingly the beginning and most sacred duty of every successive age, and especially the leaders of it, to know and lay to heart as the merely link by which Eternity lays agree of it, and it of Eternity.

See also [edit]

- Smashing man theory

- Historiography of the French Revolution

- Historiography of the U.k.

- John Sterling

- Nouvelle histoire

- Philosophy of history

- Ralph Waldo Emerson

- Übermensch

References [edit]

- ^ "Thomas Carlyle · George Eliot Archive". georgeeliotarchive.org . Retrieved 5 Feb 2022.

- ^ "The Project Gutenberg eBook of Encyclopædia Britannica, Volume Five Slice III - Capefigue to Carneades". world wide web.gutenberg.org . Retrieved five February 2022.

- ^ "Thomas Carlyle's The French Revolution". victorianweb.org . Retrieved 5 Feb 2022.

- ^ "The Project Gutenberg eBook of Encyclopædia Britannica, Book V Slice III - Capefigue to Carneades". world wide web.gutenberg.org . Retrieved 5 Feb 2022.

- ^ Campbell, Ian. "THE CARLYLE Social club OF EDINBURGH." Carlyle Newsletter, no. 2, Saint Joseph'southward Academy Press, 1980, pp. 27–30, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44945580.

- ^ Schapiro, J. Salwyn. "Thomas Carlyle, Prophet of Fascism." The Journal of Modern History, vol. 17, no. two, University of Chicago Press, 1945, pp. 97–115, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1871955.

- ^ "The Norman and Charlotte Strouse Edition of the Writings of Thomas Carlyle titles from Academy of California Press". www.ucpress.edu . Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ^ "The Carlyle Letters". The Academy of Edinburgh . Retrieved five February 2022.

- ^ Campbell, Ian (ten Apr 2012). "Retroview: Our Hero?". The American Interest . Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f 1000 h i j k l "Thomas Carlyle and Dumfries & Galloway". D&One thousand online . Retrieved ix July 2020.

- ^ a b "Carlyle – The Sage of Chelsea". English Literature For Boys And Girls. Farlex Gratuitous Library. Retrieved 19 September 2009.

- ^ "Among these apprehensive, stern, earnest religionists of the Burgher phase of Dissent Thomas Carlyle was built-in." – Sloan, John MacGavin (1904). The Carlyle Country, with a Study of Carlyle's Life. London: Chapman & Hall, p. 40.

- ^ "As a 'double-goer', perplexing strangers in foreign parts as well as at home, the 'Apostle' was occasionally an innocent, inadvertent nuisance to 'our Tom'." – Wilson, David Alec (1923), Carlyle Till Marriage 1795 to 1826, London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., pp. 42–43.

- ^ a b Lundin, Leigh (20 September 2009). "Thomas Carlyle". Professional Works. Criminal Brief. Retrieved twenty September 2009.

- ^ "Who2 Biography: Thomas Carlyle, Writer / Historian". Answers.com. 2009. Retrieved 19 September 2009.

- ^ Nichol, John (1892). Thomas Carlyle. London: Macmillan & Co., p. 49.

- ^ D. Daiches (ed.), Companion to Literature 1 (London, 1965), p. 89.

- ^ Quoted in M. H. Abrams, The Mirror and the Lamp (Oxford, 1971), p. 217.

- ^ Shell, Hanna Rose (2020). Shoddy: From Devil's Dust to the Renaissance of Rags. Chicago: University of Chicago. pp. 44–48. ISBN9780226377759.

- ^ a b I. Ousby (ed.), The Cambridge Guide to Literature in English (Cambridge, 1995), p. 828.

- ^ "Everlasting No, The." In: Reverend James Wood (ed.), The Nuttall Encyclopædia, 1907.

- ^ "Everlasting Yea, The." In: Reverend James Wood (ed.), The Nuttall Encyclopædia, 1907.

- ^ "Sorrow, Worship of" In: Reverend James Forest (ed.), The Nuttall Encyclopædia, 1907.

- ^ "Silence, Worship of" In: Reverend James Wood (ed.), The Nuttall Encyclopædia, 1907.

- ^ I. Ousby (ed.), The Cambridge Guide to Literature in English (Cambridge, 1995), p. 350.

- ^ Cumming, Mark (2004). The Carlyle Encyclopedia. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, p. 223 ISBN 978-0-8386-3792-0

- ^ Marcus, David D. (1976), "The Carlylean Vision of 'Tales of 2 Cities'", Studies in the Novel 8 (i), pp. 56–68.

- ^ Delaura, David J. (1969). "Ishmael as Prophet: Heroes and Hero-Worship and the Self-Expressive Basis of Carlyle's Fine art", Texas Studies in Literature and Linguistic communication, Vol. 11, No. 1, pp. 705–732.

- ^ Carlyle, Thomas (1869), On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History, London: Chapman and Hall, 301.

- ^ a b c D. Daiches ed., Companion to Literature 1 (London, 1965), p. 90.

- ^ Quoted in E. Halevy, Victorian Years (London, 1961), p. 40.

- ^ "Reviews from the Neue Rheinische Zeitung Politish-Ökonomische Revue No. 4" contained in the Nerveless Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 10 (International Publishers: New York, 1978) pp. 301–310.

- ^ "Reviews from the Neue Rheinische Zeitung Politisch-Ökonomische Revue No. 4" contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume x, p. 306.

- ^ Quoted in Grand. Sadleir, Trollope (London, 1945), p. 158.

- ^ Northward. Frye, Anatomy of Criticism (Princeton, 1971), pp. 21 and 325.

- ^ Carlyle, quoted in Thou. 1000. Trevelyan, An Autobiography (London, 1949), p. 175.

- ^ Carlyle, Thomas (1849). "Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question". Fraser's Magazine for Town and State. Vol. xl.

- ^ Higgins, Michael (2012). "A Strange Instance of Hero-Worship: John Mitchel and Thomas Carlyle". Studi irlandesi. A Journal of Irish gaelic Studies. two (2): 329–352. doi:x.13128/SIJIS-2239-3978-12430. hdl:10034/322207. Retrieved 3 Jan 2021.

- ^ Quoted in East. Halevy, Victorian Years (London, 1961), p. 257.

- ^ Barlow, Nora ed. 1958. The autobiography of Charles Darwin 1809-1882. With the original omissions restored. Edited and with appendix and notes past his grand-daughter Nora Barlow. London: Collins.

- ^ Hall, Catherine (2002). Civilising Subjects: Metropole and Colony in the English Imagination, 1830–1867. University of Chicago Press, p. 25.

- ^ Trella, D.J. (1992). "Carlyle's 'Shooting Niagara': The Writing and Revising of an Article and Pamphlet", Victorian Periodicals Review 25 (1), pp. thirty–34.

- ^ a b Ross, Greg (15 July 2018). "Peace and Tranquillity". Futility Cupboard . Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ^ Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

- ^ Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

- ^ I. Ousby (ed.), The Cambridge Guide to Literature in English (Cambridge, 1995), p. 154.

- ^ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter C" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ^ Grindea, Miron, ed. (1978). The London Library . Ipswich: Boydell Press/Adam Books. pp. 9–13. ISBN0-85115-098-five.

- ^ Wells, John (1991). Rude Words: a discursive history of the London Library. London: Macmillan. pp. 12–56. ISBN978-0333475195.

- ^ Wells (1991), pp. 26–31.

- ^ Heffer, Simon (1995). Moral Desperado – A Life of Thomas Carlyle. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, p. 48

- ^ Howe, Susanne (1935). Geraldine Jewsbury, Her Life and Errors. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- ^ Collis, John Stewart (1971). The Carlyles: A Biography of Thomas and Jane Carlyle. London: Sidgwick & Jackson.

- ^ Leigh Hunt, 1784–1859, Poetry Foundation.

- ^ Rose, Phyllis (1984). Parallel Lives: 5 Victorian Marriages. [Knopf]. pp. 25–44, 243–259. ISBN0-394-52432-2.

- ^ Butler, Samuel (1935). Messages Betwixt Samuel Butler and Eastward.M.A. Cruel 1871–1885. London: Jonathan Cape, p. 349.

- ^ Froude, James (1903). My Relations with Carlyle. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. On pages 21–24, Froude insinuates that Carlyle was impotent (p. 21): "She [Mrs. Carlyle] had longed for children, and children were denied to her. This had been at the bottom of all the quarrels and all the unhappiness"; (p. 22): "Intellectual and spiritual affection beingness all which he had to give [his wife]"; (p. 23): "Carlyle did not know when he married what his constitution was. The morning after his wedding-day he tore to pieces the flower-garden at the Comeley Bank in a fit of ungovernable fury."

- ^ Harris, Frank. 'My Life and Loves' (London, Corgi 1973 p232 -243. ed. John F. Gallagher) claims that Carlyle had confessed his impotence to him personally, and records an account by Mrs Carlyle'south doctor, who had examined and establish her to be a virgin after 25 years of union. Harris's information is doubted by several scholars, the editor John Gallagher noted in a footnote.

- ^ a b Mark Cumming (2004). The Carlyle Encyclopedia. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. pp. 83–. ISBN978-0-8386-3792-0 . Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ^ Carlyle'southward House. Archived 15 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine,

- ^ Conrad, Barnaby (1961). Famous Last Words. London: Alvin Redman, p. 21.

- ^ Dunn, Waldo Hilary (1930). Froude & Carlyle, a Study of the Froude-Carlyle Controversy. London, Longmans, Greenish and Co.

- ^ Carlyle, Alexander & Sir James Crichton-Browne (1903). The Nemesis of Froude: A Rejoinder to James Anthony Froude'southward "My Melations with Carlyle". New York and London: John Lane: The Bodley Head.

- ^ "Volition and Codicil of Thomas Carlyle, Esq.", in My Relations with Carlyle, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, p. 73.

- ^ Pieterse, Jan P. Nederveen (1989). Empire and Emancipation: Power and Liberation on a World Scale. Praeger. ISBN978-0275925291.

- ^ Frankel, Robert (2007). Observing America: The Commentary of British Visitors to the United states, 1890–1950 (Studies in American Idea and Culture) . University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 54. ISBN978-0299218805.

Thomas Carlyle was perhaps the kickoff notable Englishman to enunciate a belief in Anglo-Saxon racial superiority, and, as he told Emerson, among the members of this select race he counted the Americans.

- ^ Paring, Megan; Kerry, Paul; Pionke, Albert D. (2018). Thomas Carlyle and the Idea of Influence. Fairleigh Dickinson University Printing. p. 130. ISBN978-1683930655.

- ^ Modarelli, Michael (2018). "Epilogue". The Transatlantic Genealogy of American Anglo-Saxonism. Routledge. ISBN978-1138352605.

- ^ Cumming, Mark (2004). The Carlyle Encyclopedia. Fairleigh Dickinson Academy Press. p. 252. ISBN978-1611471724.

a Jew is bad but what is a Sham-Jew, a Quack-Jew? And how tin can a existent Jew ... try to exist Senator, or fifty-fifty Citizen of any Country, except his own wretched Palestine, whither all his thoughts and steps and efforts tend,-where, in the Devil's name, let him arrive as soon equally possible, and make us quit of him!

- ^ Eisner, Volition (2013). Fagin The Jew 10th Anniversary Edition. Dark Horse Comics. p. 123.

- ^ Kaplan, Fred (1993). Thomas Carlyle: A Biography. Academy of California Press. ISBN978-0520082007.

Carlyle'due south active anti-Semitism was based primarily upon his identification of Jews with materialism and with an anachronistic religious structure. He was repelled past those "former clothes" merchants ... by "East End" orthodoxy, and by "West End" Jewish wealth, merchants clothed in new money who seemed to epitomise the intense fabric corruption of Western society.

- ^ "He believed at that place was a God in sky, and that God'southward laws, or God's justice, reigned on world". – Lang, Timothy (2006). The Victorians and the Stuart Heritage: Interpretations of a Discordant Past. Cambridge University Printing, p. 119 ISBN 978-0-521-02625-three

- ^ "Part One of Religious Revival and the Transformation of English Sensibilities in the Early Ninteeenth Century by Herbert Schlossberg". victorianweb.org. 1998. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ^ Holloway, John (1953). The Victorian Sage: Studies in Argument. London: Macmillan; Landow, George (1986). Elegant Jeremiahs: The Sage from Carlyle to Mailer. Ithaca, New York: Cornell Academy Press.

- ^ a b c Cumming, Mark (2004). The Carlyle Encyclopedia, Fairleigh Dickinson Academy Press, pp. 200ff; 223.

- ^ Orwell, Review of the Two Carlyles by Osbert Burdett, The Adelphi, March 1931.

- ^ Specimen Days by Walt Whitman (1883).Specimen Days

- ^ Kinser, Brent E. (2011). The American Civil War in the Shaping of British Democracy. Ashgate. p. 14.

- ^ Johnson, Guion Griffis (1957). "Southern Paternalism toward Negroes after Emancipation". The Journal of Southern History. 23 (4): 483–509. doi:ten.2307/2954388. ISSN 0022-4642. JSTOR 2954388.

- ^ Sorensen, David R. (2014). "Carlyle's Frederick the Great and the "sham-kings" of the American South". Carlyle Studies Annual. Saint Joseph'south University Printing (30).

- ^ Straka, Gerald K. (1 November 1957). "The Spirit of Carlyle in the Old South". The Historian. twenty (1): 39–57. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.1957.tb01982.x. ISSN 0018-2370.

- ^ Roel Reyes, Stefan (12 Jan 2022). "'"There must be a new earth if at that place is to be whatever world at all!"': Thomas Carlyle'due south illiberal influence on George Fitzhugh". Journal of Political Ideologies: 1–19. doi:10.1080/13569317.2022.2026906. ISSN 1356-9317. S2CID 245952334.

- ^ Gutzke, D. (30 April 2016). United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland and Transnational Progressivism. Springer. ISBN978-0-230-61497-0.

- ^ Carlyle, Thomas. Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question.

- ^ Leonard, Thomas C. (12 Jan 2016). Illiberal Reformers: Race, Eugenics, and American Economics in the Progressive Era (Reprint ed.). Princeton University Printing.

- ^ Grierson, H. J. C. (1933). Carlyle & Hitler: The Adamson Lecture in the University of Manchester. Cambridge: The University Press.

- ^ Bentley, Eric (1944). A Century of Hero-worship, a Report of the Thought of Heroism in Carlyle and Nietzsche with Notes on Other Hero-worshipers of Modern Times. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott.

- ^ Nietzsche, Friedrich (1907). Across Good and Evil. New York: The Macmillan Company, p. 210.

- ^ Tambling, Jeremy (2007). "Carlyle through Nietzsche: Reading Sartor Resartus", The Modern Language Review, Vol. 102, No. 2, pp. 326–340.

- ^ Lippincott, Benjamin Evans (1938), Victorian Critics and Democracy: Carlyle, Ruskin, Arnold, Stephen, Maine, Lecky, London: H. Milford, Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b Steinweis, Alan (June 1995). "Hitler and Carlyle's 'historical greatness'". History Today. 45: 35.

- ^ Ryback, Timothy West. (2010). Hitler'south Individual Library: The Books that Shaped His Life. New York: Random House.

- ^ Casirer, Ernest (1946). The Myth of the State. Yale: Yale University Press. Run into also Voegelin, Eric (2001). Selected Book Reviews. The Collected Works of Eric Voegelin, Vol. Thirteen. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, pp. 156–158.

- ^ Gravil, Richard (2007). Existentialism. Humanities, p. 35; Böhnke, Dietmar (2004). Shades of Grey: Science Fiction, History and the Problem of Postmodernism in the Works of Alidair Gray. Berlin: Galda & Wilch, p. 73; d'Haen, Theo & Pieter Vermeulen (2006). Cultural Identity and Postmodern Writing. Amsterdam: Editions Rodopi, p. 141.

- ^ Carlyle, Thomas (1840), On Heroes, Hero-worship and the Heroic in History, London: Chapman and Hall, p. 90.

- ^ David One thousand. Johnson: The Lavender Scare: The Common cold State of war Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government, University of Chicago Press, 2004, ISBN 9780226404813, p. 34

- ^ Tait, Joshua (2019). "Mencius Moldbug and Neoreaction". Key Thinkers of the Radical Right: Behind the New Threat to Liberal Democracy. ISBN978-0-19-087760-vi.

- ^ Morrill, John (1990). "Textualizing and Contextualizing Cromwell", Historical Periodical 33 (iii), pp. 629–639. Examines the Abbott and Carlyle edit.

- ^

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain:Wood, James, ed. (1907). "Logic Spectacles". The Nuttall Encyclopædia. London and New York: Frederick Warne.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain:Wood, James, ed. (1907). "Logic Spectacles". The Nuttall Encyclopædia. London and New York: Frederick Warne.

Bibliography [edit]

- Chandler, Alice (1998), "Carlyle and the Medievalism of the Northward". In: Richard Utz and Tom Shippey (eds), Medievalism in the Modern World. Essays in Honour of Leslie J. Workman, Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 173–191.

- Ikeler, A. A. (1972), Puritan Temper and Transcendental Faith. Carlyle's Literary Vision, Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Printing.

- MacDougall, Hugh A. (1982), Racial Myth in English History: Trojans, Teutons, and Anglo-Saxons, Montreal: Harvest House & Academy Press of New England.

- Roe, Frederick William (1921), The Social Philosophy of Carlyle and Ruskin, New York: Harcourt, Caryatid & Company.

- Waring, Walter (1978), Thomas Carlyle, Boston: Twayne Publishers.

Further reading [edit]

- Caird, Edward (1892). "The Genius of Carlyle". In: Essays on Literature and Philosophy, Vol. I. Glasgow: James MacLehose & Sons, pp. 230–267.

- Cobban, Alfred (1963), "Carlyle'southward French Revolution", History, Vol. XLVIII, No. 164, pp. 306–316.

- Cumming, Mark (1988), A Disimprisoned Epic: Form and Vision in Carlyle'southward French Revolution. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Harrold, Charles Frederick (1934), Carlyle and High german Thought: 1819–1834. New Haven: Yale Academy Press.

- Kaplan, Fred (1983), Thomas Carlyle: A Biography. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Müller, Max (1886), "Goethe and Carlyle", The Contemporary Review, Vol. XLIX, pp. 772–793.

- Lecky, W.Eastward.H. (1891), "Carlyle's Message to his Age", The Gimmicky Review, Vol. Lx, pp. 521–528.

- Norton, Charles Eliot (1886), "Recollections of Carlyle", The New Princeton Review, Vol. II, No. 4, pp. 1–19.

- Rigney, Ann (1996). "The Untenanted Places of the Past: Thomas Carlyle and the Varieties of Historical Ignorance", History and Theory, Vol. XXXV, No. iii, pp. 338–357.

- Rosenberg, John D. (1985), Carlyle and the Burden of History. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- Rosenberg, Philip (1974), The Seventh Hero. Thomas Carlyle and the Theory of Radical Activism, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Printing.

- Slater, Joseph (ed.) (1964). The Correspondence of Emerson and Carlyle. New York: Columbia Academy Press.

- Stephen, James Fitzjames (1865), "Mr. Carlyle", Fraser'southward Magazine, Vol. LXXII, pp. 778–810.

- Stephen, Leslie (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. v (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 349–354.

- Symons, Julian (1952), Thomas Carlyle: The Life and Ideas of a Prophet, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Vanden Bossche, Chris (1991), Carlyle and the Search for Authority, Columbus: Ohio State University Press.

- Charles Edwyn Vaughan. "Carlyle and his German masters". Essays and studies: past members of the English Clan. 1: 168–196. Wikidata Q108122699.

- Wellek, René (1944). "Carlyle and the Philosophy of History", Philological Quarterly, Vol. XXIII, No. 1, pp. 55–76.

- Macpherson, Hector Carswell (1896), "Thomas Carlyle", Famous Scots Serial, Oliphant, Anderson and Ferrier

External links [edit]

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Carlyle

0 Response to "Welch, K. (2012). Family Life Now (2nd Ed.). Boston. Allyn and Bacon Where Published"

Post a Comment